Re: Industrial Foods

These professors say “We Shouldn’t Want to Eat Like Our Great-Great-Grandparents”.

The writers are correct that our large, year-round, global food supply is an astonishing success. Like the caesarean section (which has saved the life of many a mother and baby), the global food system is a miracle of steady abundance. But that doesn’t mean every birth needs a miracle operation, and it doesn’t mean every meal starting with soda and corn chips followed by an airplane dinner is a good one.

The writers acknowledge, and then simply overlook, the harm industrial food production inflicts on flavor, nutrition, soil structure, water supply, biodiversity, and agricultural workers, to name a few downstream victims. They mention, and then dismiss, the epidemic of chronic diseases caused by high quantities of high-calorie, refined foods: obesity, diabetes, and heart disease. They overlook the major causes of increased longevity: vaccines, antibiotics, and pharmaceuticals.

What do they say about the food we eat? They (or the headline writers) make fun of Michael Pollan’s simple suggestion that we think of real food as something our grandparents in the homestead kitchen (or on the Lower East Side) would recognize, and they scoff at people promoting from-scratch cooking because they are “social media influencers.” Social media influencers are only derided for being social media influencers when the speaker doesn’t like what they’re selling.

These authors are, however, selling an industrial egg-white snack by brand name, which I thought was an odd choice. (Did an editor say, can you name-check a couple of industrial foods, you know, to be…relatable?) Golly, I’ve eaten those! Good for the road. Ingredients, not bad. I hope they introduce one with an egg yolk and full-fat cheese.

The authors don’t observe, or don’t understand, the key difference between industrial and traditional methods of food processing. Long before industrial methods of food production, beginning with fire, humans altered raw ingredients with traditional methods to make foods like cheese, smoked meat, dried nuts and legumes, and fermented vegetables.

Processing raw ingredients can increase shelf life, flavor, and even nutrition (consider yogurt, brined nuts, fermented grain, otherwise known as bread, which is as tasty and digestible for humans as raw grain is not). It is strange to call yogurt ultraprocessed – it is a traditional food and minimally processed. When it’s filled with corn syrup, pectin, guar gum, and artificial colors it’s certainly a crappy recipe, but adding cultures to gently heated milk is 8,000 years old.

Traditional processing also reduces waste. After eating the chicken meat, you make broth from the bones to dig out the calcium and collagen. After making mozzarella, you have whey for low-fat ricotta. After eating, you feed the pigs and chickens the plate waste. This is one compliment industrial food pays to traditional food – they do use every last bit! The supermarket gives us a lot of soybean food-like items because the soybean oil industry produces a lot of protein-and-fiber pulp. Sometimes they use bits they had better not – you don’t feed sheep brain to cows. Cow are herbivores, who like to eat grass and forbs, and they don’t want to get mad cow disease from mad sheep.

Industrial processing, by contrast, increases shelf life but reduces flavor and nutrition. Consider orange juice, to name but one minimally processed food. After pasteurization, orange juice is stored in massive tanks. After a year or so, it contains less active ascorbic acid and tastes of nothing. It is essentially a solution of pure tasteless carbohydrate. So the makers of “not from concentrate” juice add proprietary flavor packets to make it taste like a fresh orange. I know it feeds a nation of OJ drinkers, but I still call that a loss for flavor and nutrition. Whole frozen OJ would be better.

Ultraprocessed foods, or UPF, are the result of even more extreme processing, which is anathema to flavor and nutrition. From my lay-language, real-food perspective, the conventional working definition of a UPF is pretty good: If a product has a long shelf life, contains ingredients you can’t buy, don’t cook with, and can’t pronounce, it is likely a UPF.

Foods on the borderline of this rough-and-ready definition make tough cases but that’s a quandary only for little minds. I consider homogenized UHT certified organic milk highly processed (and I greatly prefer unhomogenized, gently pasteurized, local, grass-fed milk for its freshness, flavor, texture, nutrition, and diversity) but it’s one of the best whole foods the industrial system has produced.

The difference between raw wheat and bread is considerable. When wheat is processed in the traditional manner (with yeast or sourdough, salt, and time), the result is an improvement on the raw material (for humans anyway) in flavor, texture, and nutrition. Bread made with the 1961 Chorleywood Bread Process, which short-cuts all that with high speed mixing, extra yeast, added fats, and oxidizing agents), is not an improvement on the raw ingredients. Once again, I call that a loss.

Sadly, essays hostile to the new government advice and in praise of industrial foods in this moment, early in the second Trump administration, come with an unmistakeable scent of cultural and political bias.

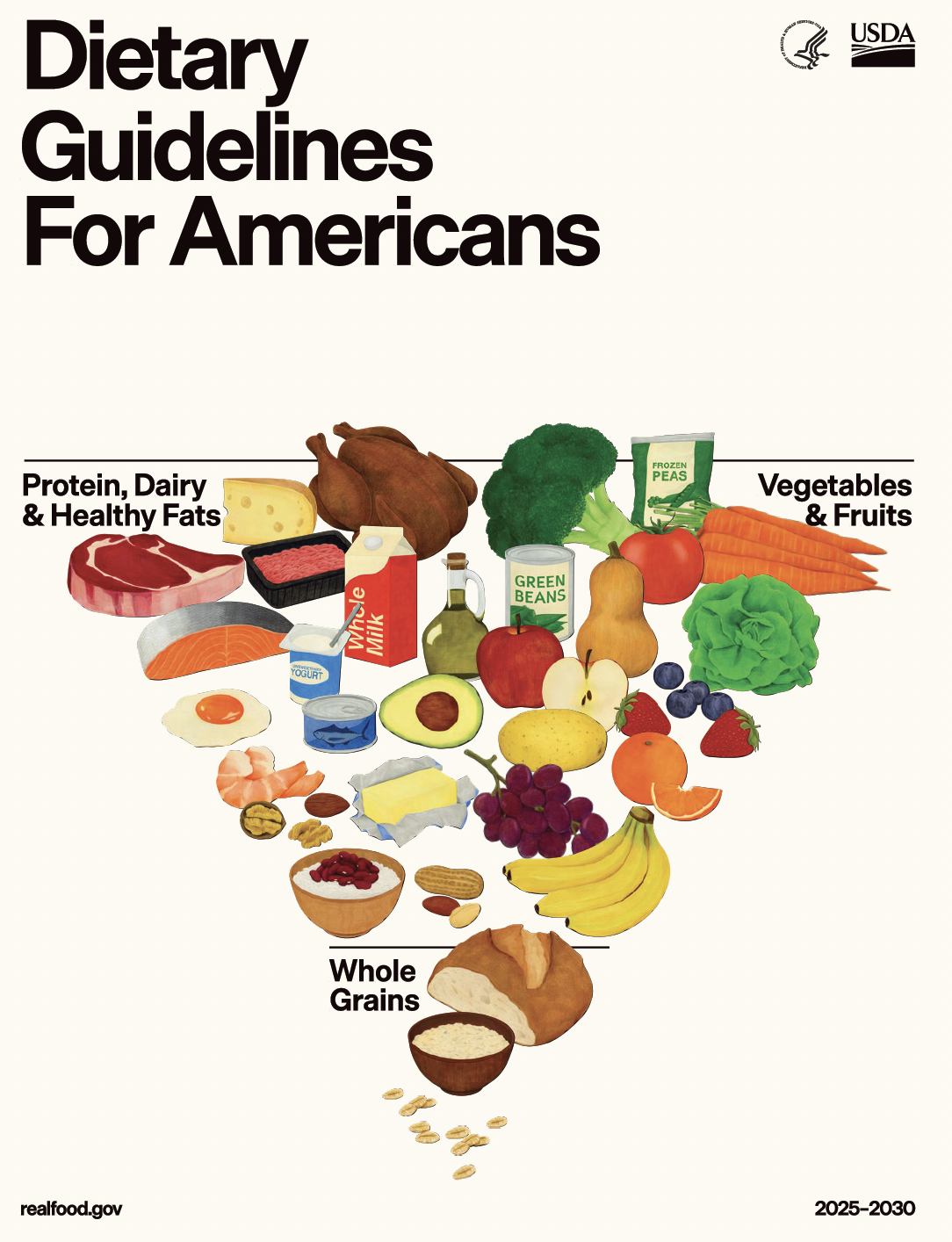

If Michelle Obama and Bruce Springsteen had done a joint appearance on the Oprah Winfrey show, backed by a nationwide summer-long Willie Nelson & Family Real Food Nation Tour, to introduce the new Real Food Pyramid, which calls for an omnivorous diet of whole foods readily available at any modern supermarket (and urges us to limit trans fats, rancid oils, sugar, and alcohol to boot), the legacy media, many academics, and all my friends would be praising it.

Hey, eaters! Wake up. We must stop fighting culture wars using ugly and dismissive labels for the people we disagree with, and start finding common ground on a better food culture in this country.

When I published Real Food: What to Eat and Why in 2006, I fantasized that one day the USDA would release dietary advice looking like my own breakfast, lunch and dinner. I never imagined it would happen and I am delighted.

The only diet that is not a fad (and I include the so-called Mediterranean diet, which is suspect on a couple of levels) is one based on moderate omnivory of whole and minimally processed foods. Whether you buy your whole eggs at the supermarket or get them from your own chickens, whether you buy tomatoes at a farmers market or the superstore, eat them fresh or jarred as salsa (more lycopene), whether you like salmon, beef or poultry (fresh or frozen), whether you buy your chick peas in a can at the discount aisle or (even cheaper) buy them in bulk and soak them yourself, whether you buy a massive block of cheddar for your kid’s lunch or a mozzarella stick wrapped in plastic – you are on the real food diet.

As for the phrase “real food,” which I adopted as a shorthand for the right way to eat, I stand by it. Read all about it Real Food: What to Eat and Why, still in print after twenty years.